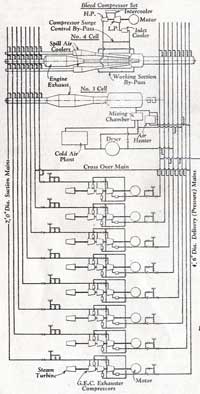

By the early sixties Dad was the engineer-in-charge of the engine test facility at Pyestock and he took me to see it a few times. It consisted of a Parsons steam turbine which used to spin eight electric motors up to mains synchronous speed and all nine then powered air compressors which pushed enormous quantities of air at up to 2,000 miles per hour into the Olympus engine wind tunnel. The total power was a little short of half a million horsepower. The steam was generated by a boiler taken from an old Battle class destroyer (hence the name Battle House for the boiler room) and the electricity was taken from the national grid but only when the Central Electricity Generating Board’s (CEGB) headquarters at East Grinstead said there was sufficient spare capacity. In practice this meant that Concorde’s engine could only be tested at night. Dad made several trips to East Grinstead presumably to liaise and negotiate with the CEGB. I suspect it was no coincidence that some areas within several miles of N.G.T.E. had gas street lighting until the early 1970s. We always knew when Dad had got to work and switched on his electric motors because the home television picture would shrink and a moment later we would hear the roar of the engines starting up even though the test facility was about two miles away from home.

My recollection of the test facility

known as the Air House is that it was of course enormous and

looked like a cross between a power station and a ship’s engine room.

The motor/compressor units were laid out in lines and were of considerable

length, 50 or 60 feet each I would think and they were surrounded by those cast

iron see-through walkways of the type to be seen in TV documentaries set in old

fashioned factories or prisons. (Photographs

added 2 June 2007). In one corner of the room at a vantage point

looking down on the machinery was the control gallery. Quite what was in it I do

not know apart from the main on/off switches. These were the days before

computer control and telemetry and in fact machine readings were taken by hand

by people who walked around the complex noting down individual gauge readings

and reporting back to the control desk at half-hourly intervals. The object of

the exercise was to develop the Olympus engine (which started life at 10,000

pounds of thrust and which was giving twice that by the late fifties) to give

sufficient power to get Concorde across the Atlantic economically (for its day)

and with range to spare. My recollection is that the aim was to get 42,000

pounds of thrust from the engine but as Concorde is said to have only 38,000

pounds per engine either my recollection is at fault or the ideal target was

never met. The economic standards for airliners of the day were set by the

Boeing 707 and de Havilland Comet and the aim was to ensure that Concorde

achieved a similar fuel consumption. In this it succeeded but what no one seemed

to account for was the development of more efficient by-pass and three-spool engines. See below.

My recollection of the test facility

known as the Air House is that it was of course enormous and

looked like a cross between a power station and a ship’s engine room.

The motor/compressor units were laid out in lines and were of considerable

length, 50 or 60 feet each I would think and they were surrounded by those cast

iron see-through walkways of the type to be seen in TV documentaries set in old

fashioned factories or prisons. (Photographs

added 2 June 2007). In one corner of the room at a vantage point

looking down on the machinery was the control gallery. Quite what was in it I do

not know apart from the main on/off switches. These were the days before

computer control and telemetry and in fact machine readings were taken by hand

by people who walked around the complex noting down individual gauge readings

and reporting back to the control desk at half-hourly intervals. The object of

the exercise was to develop the Olympus engine (which started life at 10,000

pounds of thrust and which was giving twice that by the late fifties) to give

sufficient power to get Concorde across the Atlantic economically (for its day)

and with range to spare. My recollection is that the aim was to get 42,000

pounds of thrust from the engine but as Concorde is said to have only 38,000

pounds per engine either my recollection is at fault or the ideal target was

never met. The economic standards for airliners of the day were set by the

Boeing 707 and de Havilland Comet and the aim was to ensure that Concorde

achieved a similar fuel consumption. In this it succeeded but what no one seemed

to account for was the development of more efficient by-pass and three-spool engines. See below.I have two particular memories from the time that Dad ran those engine tests. Firstly that the air flow was very difficult to turn off. It suffered the equivalent of ‘water hammer’, the same as if you close off the flow at your basin tap by suddenly capping it with your hand, or similar, the shock wave will make the pipes go bang. Shutting off air flowing at twice the speed of sound quickly tended to break the compressors. Apparently the engineers at various companies including Rolls Royce had supplied equipment designed to do the job but all were unsatisfactory. Dad designed a system mounted in a Dexion rack the size of a small wardrobe full of (as I recall) pipes and aneroid barometers which did the trick at a cost under £100. Dad always did say a good engineer was someone who could make for a penny what any damned fool could make for a shilling!

The other episode was somewhat more dramatic. One evening, I forget just when, Dad came home late at night looking grey and unwell. I remember Mum being most concerned and I think she for a moment thought he must have stopped for a beer or two on the way home even though that is something I don’t think he ever did. When he’d calmed down a bit he told us what had happened. Apparently one of the men taking 30 minute interval meter readings from the air compressors thought one of them should be reported sooner rather than later and as a result Dad had rushed to the machine to see for himself. He put his ear to the engine casing (no wonder he went deaf!) and decided that the main thrust bearing was in serious trouble. He ordered everyone to run while he went back to the control room to close the system down. However he was too late and the main compressor shaft broke free from its casing and hurtled across the building wrecking most of the other compressors as it went. Fortunately because of the quick thinking of the meter reader and the instant diagnosis of the fault everyone had time to get out of the way and no one was hurt. When I saw the scene later it was one of complete devastation and it set the engine tests back six months.

At a later phase of Concorde’s development Dad used to spend alternate weeks in France. He would fly to Paris in the evening and get the overnight sleeper train to Toulouse. I think it would be true to say that Dad didn’t have the highest opinion of the French aviation industry’s abilities. He would complain that it could take up to six months to translate the various technical reports sent from Toulouse and neither was he very surprised that various key components that the French were supposed to build were delivered marked ‘Made in U.S.A.’. One of the lasting legacies of the commuting to France is the supply of duty free whisky and brandy that still resides in my drinks cabinet, neither father nor son being much of a spirits drinker.

Dad was not I believe heavily involved in flight testing however one of my memories is of him telling me just how strong Concorde was. He said that in the period when we were trying to sell the plane to foreign airlines a Pan-American crew was invited to loop Concorde over the Atlantic. Their response was to the effect that that would be silly as an airliner would break up during such a manoeuvre but they were persuaded that Concorde was an exception. Over the years I began to doubt this story and wondered if perhaps Concorde had been rolled rather than looped, rolling being a fairly easy accomplishment compared to a loop. I was therefore pleased to read newspaper commemorative articles during the final week of Concorde’s commercial life, evidence that I had not imagined it after all.

I managed to get inside Concorde myself just once, a quick end-to-end walk-through on the ground. I did however see it flying many times, once with full reheat on only a few feet above my own house roof in Connaught Road, Fleet. That would be in 1970 or 1971. I think it was in 1969 that I went to the flying display at Farnborough and the weather was absolutely filthy with driving rain and poor visibility. Concorde was due to fly in from Filton and it was doubtful whether it could make it. However it managed to make a couple of touch-and-go passes before disappearing into the low clouds. When I got home I discovered that conditions were so poor back at Filton that Concorde could not land there and the only runway within range that was both long enough and had the requisite blind landing equipment was Heathrow. As you may imagine it was the front page news in all the papers next day.

Concorde was undoubtedly a magnificent achievement and all the more so when so much of the design work was done by practical experiment and slide-rules. I cannot finish this set of recollections without mentioning Dad’s great friend Eric Lewis with whom he started his career on jet engine development in the late 1940s. Eric’s expertise led him in other directions doing a great deal of work on TSR2 and pursuing his ideas to make quieter jet engines. This culminated in the Rolls Royce RB211 ‘three-spool’ engine. This new type of jet engine became the norm for all current jet airliners. Despite his work on that project at the very same time that Concorde was being prepared for service, Eric was, if I remember correctly, appointed to be the Director of Production for Concorde when the expectation was that it would be mass produced. I recall Dad saying about Eric’s predecessor in that role that “he couldn’t manage a match box factory”. Fortunately that fact was recognised and equally fortunately I cannot remember his name - so I am probably out of reach of the libel laws. Eric still lives in Farnborough in the same house that he bought in 1958.

Disclaimer: Everything above is taken from memory of conversations around the family meal table and occasional visits to the Concorde test facilities. Whilst most of it is known to be true the forty intervening years may have had some effect on the precision of the detail. Two and a half years after recording the above notes I made a belated visit to Farnborough’s AirSciences museum which attempts to preserve the memory and artefacts of the N.G.T.E. and R.A.E.’s pioneering work on and research into aviation. Here are some photographs taken there.

Malcolm Knight

26 October 2003